Just how good is the x86 cmov instruction?

Suppose you want to write the following code inside a performance critical loop:

if(cond) {

foo = bar;

}

where foo is a local variable (of some simple type, like int),

and bar is either

a local variable, or a simple memory location (such as A[i]).

Such a code is likely to be found for example in a

Kadane's algorithm

implementation.

There are two standard ways for an x86-64 compiler to translate

this conditional into Intel assembly, namely a cmov

instruction, or a conditional branch paired with a regular mov.

To make this example more concrete I will focus on this particular code:

int j;

int res = 0;

for(j = 0; j < n; ++j) {

if(A[j]) {

res = j;

}

}

GCC version 4.8.2 emits the following code for the if

at -O3 (gas' assembly notation):

movl (%rdi,%rcx,4), %r9d

testl %r9d, %r9d

cmovne %ecx, %eax

Clearly the compiler stores the location of A in %rdi,

the value of j in %rcx (%ecx), and res in %rax (%eax).

We may however ask it to forget about the cmov instruction by

using the following command line parameters in addition to -O3:

-fno-tree-loop-if-convert

-fno-tree-loop-if-convert-stores

-fno-if-conversion

-fno-if-conversion2.

Then we will obtain the following assembly:

movl (%rdi,%rcx,4), %r9d

testl %r9d, %r9d

je .L4

movl %ecx, %eax

.L4:

To make this example more interesting let's feed the compiler

with more data. GCC (and others probably too) implements

a mechanism allowing the programmer to specify that a condition

will likely/unlikely be true during the runtime. In our case

it would look like this (assuming that we are expecting

A[j] to be generally false):

int j;

int res = 0;

for(j = 0; j < n; ++j) {

if(__builtin_expect(A[j], 0)) {

res = j;

}

}

The corresponding GCC output:

movl (%rdi,%rcx,4), %r9d

testl %r9d, %r9d

jne .L20

.L14:

/* Other code */

.L20:

movl %ecx, %eax

jmp .L14

We are of course free to put 1 in the place of 0 whenever

we expect A[j] to be true most of the time:

int j;

int res = 0;

for(j = 0; j < n; ++j) {

if(__builtin_expect(A[j], 1)) {

res = j;

}

}

And the corresponding GCC output (note the speculative

movl execution!):

movl %eax, %r8d

movl (%rdi,%rcx,4), %r10d

movl %ecx, %eax

testl %r10d, %r10d

je .L29

.L24:

/* Other code */

.L29:

movl %r8d, %eax

jmp .L24

This way we obtain four versions of the program which I will call cmov, branch, branch_0 and branch_1. One might ask why there is no cmov_0 and no cmov_1, but it is due to the fact that in cmov's case the compiler ignored the likely/unlikely hints.

The point of this excercise is to measure their execution

speed, but this of course depends on the contents of

the A array. So let's fill it with random independent

identically distributed zeros and ones,

manipulating the probability of one (the probability

that the if's condition will be true).

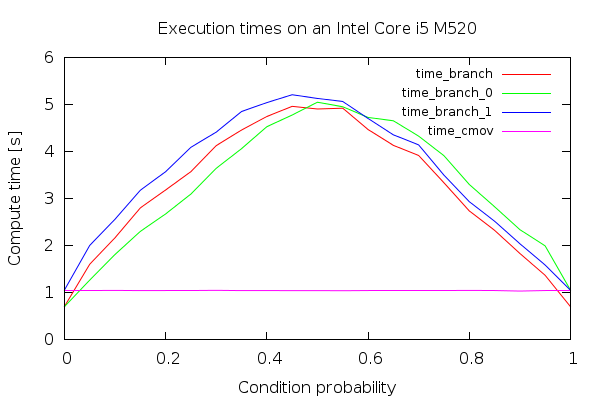

These are the results I obtained on my machine. It is the execution time, so the lower the better:

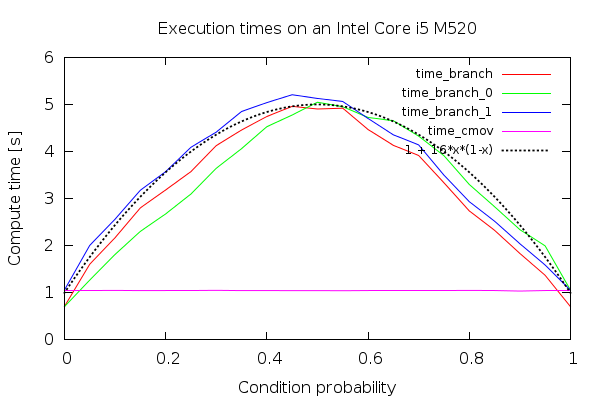

Three interesting facts can be read from this plot:

- The

cmovinstruction is generally faster. It is also immune to the probability - However the branch version is faster for stable, predictable conditions.

- The branch versions take approximately

p*(1-p)time to execute. The nice parabola-alike looks is approximately the variance of the distribution thatAwas sampled from.

The "visual proof" for the third fact:

To conclude, GCC emits cmov by default, and it seems like

a reasonable choice, at least on my Intel Core i5. However,

it is not the optimal solution for stable,

predictable conditions.